After a difficult start to the year, robotics and automation stocks are showing signs of stabilization. The ROBO index is up 15% so far in the final quarter of 2022.1 We recently spoke with our strategic advisor Morten Paulsen, head of equity research at CLSA based in Tokyo, who has been advising investors in Asian factory automation companies for more than 20 years. In this interview, we discuss why investors should prepare for the best buying opportunity for robotics since March 2020, the deflationary impact of automation technology, and how Asia is likely to continue to play a major role in the space.

Jeremie Capron, ROBO Global Director of Research: I would like to start this discussion with some big-picture questions. A lot has changed since your last interview with us in 2019[VB1] . We’re now in a macro environment of rising interest rates, geopolitical risk, the highest inflation rates since the ’70s, and a possible global recession. How is all of this affecting the demand for robotics and automation?

Morten Paulsen, CLSA Head of Equity Research: That’s a lot of discussion points. Let’s start with inflation and the role robotics and automation play.

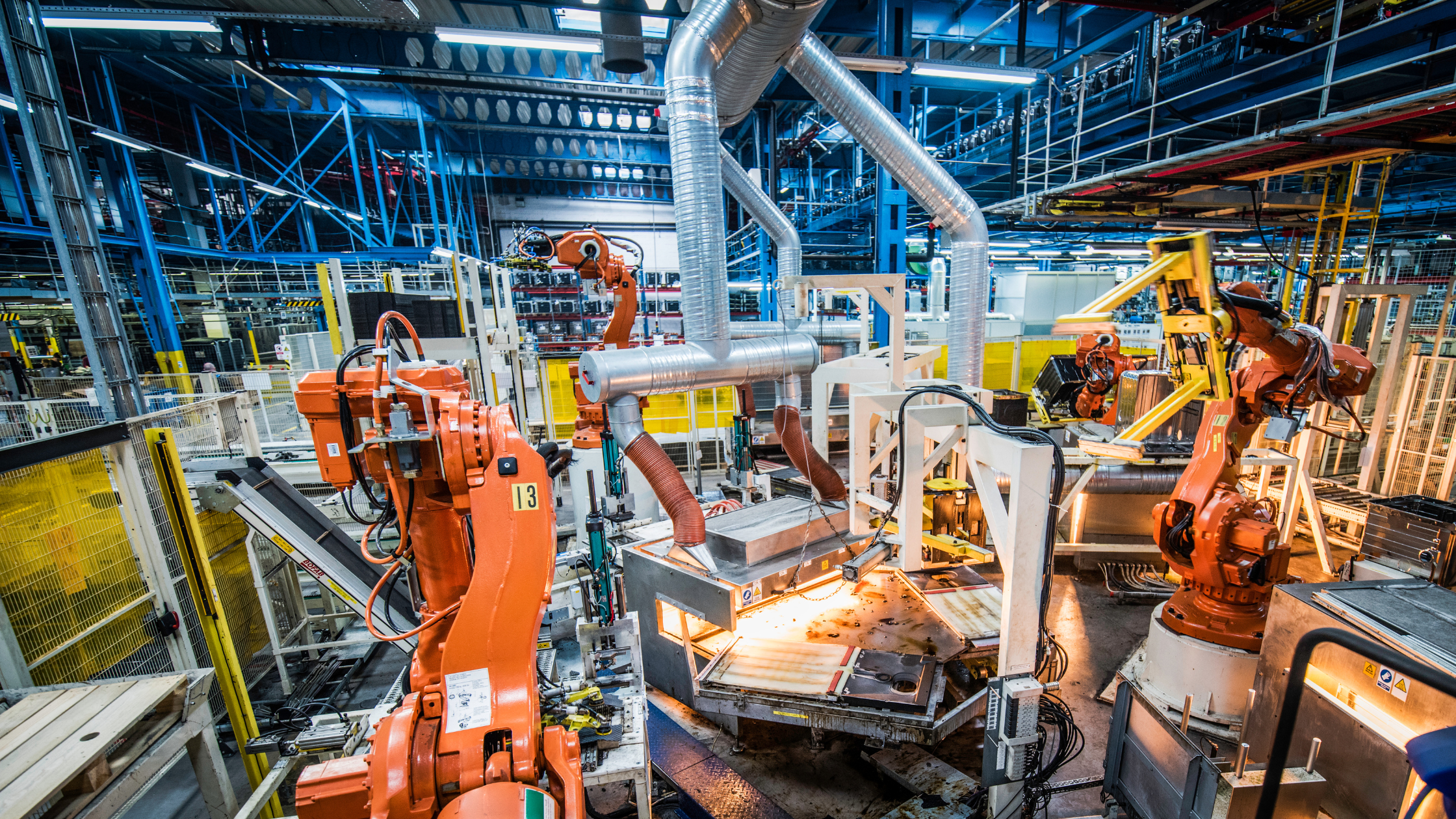

Industrial automation is a deflationary force. Robots and automation equipment enable manufacturers to lower marginal unit costs. Robots don’t put upward pressure on labor costs either, and that is another way of curbing inflationary pressure. I like to call robots “inflation fighters” for those reasons.

In the environment we’re in today, I would argue that the only deflationary force we have left are robots and similar technologies advancing labor efficiency.

In the old system, before 2017 or so, countries like the US could import deflation through trade with low-cost producers like China. That system is now broken. Production costs in China are going up. On top of that, you have border tariffs and higher shipping and logistics costs. The US and Europe are now importing inflation, not deflation. Demographics and a shrinking workforce are also fueling inflation.

JC: The US introduced the Inflation Reduction Act a few months ago. Is that a step in the right direction?

MP: Some will argue that subsidies only create inflation as you pump more money into the system, and I have a lot of sympathy for that view. However, a significant portion of the Inflation Reduction Act is aimed to stimulate the supply side of the economy. According to data compiled by the AMT, more than $88 billion is directly supporting manufacturing in the US.

Helping companies improve labor efficiency through automation will allow them to better compete in a more inflationary environment and should bring prices down and jobs back at the same time.

Supply-side policies aimed to stimulate investments in efficiency are a part of the solution. The way I see it, the Inflation Reduction Act is far from perfect, but it is a step in the right direction.

JC: Inflation is also causing interest rates to go up. Aren’t higher interest rates making it harder for companies to invest in robotics?

MP: According to textbook economics, rising interest rates are negative for capital expenditure. However, if you run a historical correlation analysis between interest rates and automation investments, you get a positive correlation coefficient ― meaning that robot and automation investments are high when interest rates are high.

JC: So that’s the opposite of the textbooks. How would you explain that?

MP: It means that manufacturers won’t rush out to buy equipment just because interest rates are low. Demand for automation equipment is more tied to capacity utilization ratios and tightness in the labor market.

Currently, the labor market is extremely tight, explaining why robot demand is at record high levels. Everything I heard at the IMTS show in Chicago back in September would suggest that labor shortage is a real issue and a real obstacle for bringing manufacturing back.

We have talked about re-shoring for many years now, but apart from a few examples here and there, it wasn’t a substantial movement. The net increase of imports of manufactured goods would dwarf the amount of production that was brought back. I believe that could be changing now. Manufacturers want to localize manufacturing and shorten supply chains. This is also an opening for investments in “near-shoring” locations such as Mexico.

JC: If manufacturers are “re-shoring,” isn’t that negative for China? China is, after all, the world’s largest market for automation equipment.

MP: I don’t think the world will stop buying Chinese manufactured goods. The country has significant advantages in terms of scale and manufacturing knowledge that will be hard to replace.

However, I do think manufacturers outside of China are applying a higher risk premium on Chinese-made components. Over the next decade, I do believe that a higher percentage of the incremental manufacturing capacity will be added outside of China.

JC: Back in 2007 or 2008, you published a landmark report called “Automating Asia,” where you correctly predicted that Asia would become a major driver for global automation over the next decade. You sound less upbeat about Asian automation today, am I right about that?

MP: Well, a lot has changed since 2008. China’s robot density in manufacturing is now fairly close to that of the US and Western Europe. As the market matures, we should expect growth rates to slow down.

That said, just like the United States, China is facing a labor shortage. Birth rates in China dropped dramatically in the ’80s due to the one child policy, and that is now resulting in a sharp drop in labor entry and labor participation. That is again leading to higher labor cost and direct labor shortage. China is looking to robots as the solution to their problems.

Beyond China, I still think Asia will remain a growth driver as the region offers a lot of opportunities to increase the level of automation in manufacturing. We have big countries like India where the shift to automated manufacturing is just starting. I also see Southeast Asia as a beneficiary of companies shifting capacity out of China.

JC: What do you expect in terms of growth rates for automation globally and in China going forward?

MP: Economic growth is slowing down. I believe the April-June quarter marked the cyclical peak for global machinery orders. China peaked out 12 months before the rest, more specifically in the April-June quarter of 2021.

China was the first market to recover after Covid, so an earlier peak could be expected. However, in the second half of 2021, the country faced a lot of headwinds. It started with the crackdown on big tech companies, then we had problems in the construction industry around the Evergrande crisis. That was again followed by power shortages and rolling blackouts. For China, 2021 was completely a story of two halves. 2022 was supposed to be a recovery year, but Covid lockdowns in Shanghai and other cities put an end to that anticipated recovery.

I thought China would have a stronger recovery in the second half of 2022 coming out of lockdowns, but that didn’t happen. The mood on the ground is not good. People are worried that lockdowns could happen again, and that is having a negative impact on consumption.

I see mixed trends depending on end markets. On the positive side, the automotive industry recovered fast, and the industry is investing heavily in EVs and electrification. On the negative side, we’re not seeing much investment going on in smartphones, PCs, etc. at the moment. Chinese exporters are also nervous about weaker end markets.

JC: And what about Japan? Is the weaker yen making it more attractive to produce in Japan?

MP: Japan has a cheap yen, a world-class industrial automation sector, and a talented workforce. It’s hard for me to see why the country wouldn’t be a highly competitive manufacturing nation. So far, the weaker yen hasn’t led to much of a capex spending boom in Japan, but I think that could change.

It’s hard to be upbeat on Europe at the moment given the energy situation and the impact that could have on consumption and manufacturing. However, I think Japan along with North America could be one of the more promising markets over the next 12 months.

JC: In our previous interview back in March 2019, you said 2020 would be a recovery year for robotics and automation demand, and you also said 2019 would be the best time to buy. In hindsight, those predictions were fairly good. The ROBO index is up 15% so far in the final quarter of 2022. What is the next buying opportunity for automation?

MP: Back in 2019, I wasn’t expecting a global pandemic to hit us in 2020, so I can’t say everything went as planned. Currently, markets are under a lot of stress given geopolitical uncertainty, rising interest rates, and cyclical contraction.

The world may look different, but the attractiveness of automation is arguably even better than what it was in the previous cycle.

I do think we’re approaching the best buying opportunity for robotics and automation since March 2020. Once we enter the second half of 2023, I would expect a number of key leading macro-economic indicators to stabilize or bottom out. That could lead to a rapid turnaround in sentiment, so in my opinion, investors have a clear six-month window to get back into the sector at a low price.

1 Data As of 11/29/22